Education Revolution: The Emergence of Charter Schools in the US

In August 2025 of this year, my for-profit education company, Pantheon Prep, landed a contract with a public high school in California. Since then, we’ve been handling all standardized testing prep, from School Admissions Tests (SAT) to Advanced Placement (AP) exams, as well as debate coaching, on the school’s behalf. The turnout for these programs was incredible: hundreds of students showed up to our sessions to take advantage of Pantheon Prep’s services. Despite the obvious benefits and overwhelming need, public schools are anything but receptive to such programs. In fact my team of a hundred interns had to contact three hundred schools to receive our first contract.

My team was either simply hung up on by principals or secretaries or treated with nasty attitudes. Even in the cases where we were pushed up to upper management, we were treated poorly. I remember one particular instance when a head of a district scheduled a meeting with me and one of our employees, failed to show up to the meeting, and blamed us for not scheduling a meeting in person. She then proceeded to schedule two more meetings with us: one of which she didn’t show up to and the other she attended with her camera off and clearly distracted. The worst case, however, was when the vice chair for a school district preached to us for an hour and thirty minutes about “brainwashing” by the public schools and the inaccuracies of Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory (he was very clearly anti-Darwinian.) To hear such rejection of basic scientific principles by a man with so much influence in education and politics was alarming at the least. To me, it became apparent that public schools, like the rest of the government, are slow and uncompromising entities motivated only by their own survival. I was sure that public schools did not work nearly as well as charter schools when it came to economic development.

So it was a matter of curiosity when I picked up an article detailing praise for the public school system and disdain for charter schools. Charter schools, in essence, are publicly funded but independently operated institutions designed to foster innovation within the public education system. The birth of the charter school was messy, politicized, and spurned by its originator, Albert Shanker, the former head of the American Federation of Teachers. Shanker’s journey to create charter schools began on a trip to Germany. In a small town, he encountered a school in which teachers managed, created the curriculum for, and taught the students. The students were also chosen by the teachers to be a part of the program. In turn, the standardized test scores for the school’s cohort were significantly above average. This journey instilled a realization in Shanker: teachers are the ones with experience and ideas, and they lack the opportunities to implement them. In 1988, he was the first to mention the term ‘charter schools’ in print journalism, and, using his political power, Al Shanker promoted charter schools as the innovative forefront of American education.

Unfortunately, his idea of charter schools was interpreted differently by many in the education industry, resulting in the lack of a unified approach to implementation. The biggest roadblock for Shanker’s dream was Ronald Reagan. Reagan, who agreed with the idea of improving public schools through a charter school-esque approach, held a different vision when it came to charter schools. Rather than believing in empowering teachers to make administrative decisions for the school as a whole, he believed in the power of the free market to dictate the offerings of the school. Reagan pushed for deregulation, accountability based on results rather than rules, and funding that follows the student. Ultimately, Reagan’s enormous influence triumphed, taking the reins of the charter school movement away from Shanker. Reagan’s advocacy of creating a publicly funded but independently run school designed to bring market-style efficiency and innovation to education came true, and it shows in the way the charter schools structure their curriculum versus public schools.

But to understand charter schools in the United States, a general understanding of its legislative history is necessary. The first major legislative step came in 1991, when Minnesota passed the nation’s first charter school law, creating a legal framework for publicly funded but independently managed schools. A year later, in 1992 the country’s first charter school opened: City Academic High School in St. Pail, Minnesota. The school still has its doors open today and more closely embodies Shanker’s original vision: small class sizes, teacher-led governance, and a focus on alternative education pathways for students who had fallen behind in traditional settings. Meanwhile, California became the second state to pass a charter school law, marking the beginning of a westward expansion that would define the movement’s next decade. By 1993, momentum accelerated: Colorado, New Mexico, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Massachusetts enacted their own charter legislation. The Federal Charter Schools Program, passed in 1994, injected national recognition and funding into the model, establishing grants to support startup costs for new charter schools. The mid-1990s was a tsunami of legislative adoption, with over a dozen states (including Texas, Florida, North Carolina, and New Jersey) joining the movement between 1955 and 1956. What began as a localized experiment in Minnesota became a nationwide movement of educational reform with bipartisan support.

1997 was a tremendous year for the charter school movement. President Bill Clinton called for the creation of three thousand charter schools by 2002 in his State of the Union Address. In his address, Clinton stressed the importance of charter schools serving as a supplement to public schools rather than a complete replacement. Following his speech, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee passed charter laws, and the nation’s first charter management network, Aspire Public Schools, was founded in 1999 in California, introducing the concept of scalable, multi-school operations. After the end of Clinton’s term, in 2002, President George W. Bush reauthorized the Federal Charter Schools Program under the No Child Left Behind Act, cementing performance accountability and test-based funding as key tenets of the movement. By 2006, more than 1 million students were enrolled in charter schools nationwide. By 2009, a standardized rubric was created, “Model Charter School Law,” which rated each state’s charter framework based on autonomy, accountability, and funding equity. This model allowed policymakers and investors to evaluate states’ openness to charter innovation, effectively introducing competitive benchmarking into the education sector.

In the 2008 presidential election, both Barack Obama and John McCain endorsed charter expansion, linking it to American competitiveness and educational choice. Under President Obama, the Race to the Top program incentivized states to reform education laws to access federal grants, which triggered a second growth surge. By 2011, charter enrollment hit 2 million students, and Maine became the 40th state to adopt charter legislation. The 2010s represented the decade of normalization. Only five states were left without charter laws. Federal funding for charter schools reached $440 million by 2018 ($500 million as of Sep 24th 2025), supporting over 7,000 schools serving nearly 3 million students. Polling reflected broad acceptance: a 2016 national study found that 78% of parents supported having a charter option available in their district.

With bipartisan support, a rapidly growing movement, and hundreds of millions of dollars in funding, charter schools seem to be on a dominating track, set to eventually surpass the public school system. This understanding of public versus charter schools is fundamental to determining what is best for Economic Development as a whole. As Americans, it is our civic duty to choose what we as individuals believe is the optimal choice for our country. In the frame of economic development, education is one of if not the most powerful determinant of a nation’s prosperity. Education is an economic elevator, quality education fuels pathways to greater opportunity and progress. Higher educational attainment is associated with higher earnings, longer productive lives, better physical and mental health, resilience and adaptability, and personal development and fulfillment. Education remains unique for human and social capital development, driving long-term economic growth. Countries with higher education tend to pay workers higher wages, with the increased pay due to a smaller labor supply capable of operating in those industries, and the required education and training carrying significant costs. How that education is implemented, is everything. Charter schools promise change in an unsuccessful status quo by bringing a new approach to education through differing fundamental theories and execution. Can charter schools really pull through with their promise, and if so, in what ways could it further America’s economic developmental goals.

A major differentiator between charter and public schools comes down to curriculum, which serves as one of the factors of analysis to reach a conclusion on which is better for the US’ economic developmental goals. Individual charter school programs and corporations host different curriculums, making comparison between public and charter schools difficult. A good metric to use, however, would be the leading charter school franchise: the Knowledge is Power Program (KIPP) Foundation. KIPP boasts 279 schools with an aggregate 122,319 students throughout PreK to 12th grade. Of these students, 53% are African American, 88% are eligible for federal free or reduced price lunch (FRPL), 13% receive special education services, and 20% are designated as English Language Learners (ELL). KIPP schools’ standard curriculum consists of classes from 7:25 am to 5:00pm, a “personalization block,” problem based student-led math instruction, explicit college and career readiness coursework (dual-enrollment classes and AP focus), and “exit tickets,” which serve as a few differences from the public school curriculum.

Public schools on the other hand, operate on a standard 180 day year with shorter days, typically averaging 6.9 hours a day of total school time. KIPP schools often use a longer school day, more school days per year, and additional instructional time when compared to typical public schools. The rationale behind this is that more instructional time allows for greater opportunities for deeper mastery, remediation, and enrichment of concepts. This emphasis on understanding thoroughly before moving on also aids in faster curriculum due to in depth understanding of fundamental concepts.

Personalization blocks are good examples of this approach. KIPP schools have dedicated times, around 45-70 minutes, in which students receive specific assistance in weak points. Rather than the majority of public schools which simply teach, revise, test, and move on, KIPP Foundation places an emphasis on concept clarity through the teacher deciding when to move on and where to help students. Problem-based student-led math instruction shifts away from teacher-centered direct instruction to student problem-exploration first. According to KIPP Baltimore, “mathematical ideas are the outcomes of the problem-solving experience rather than the elements that must be taught before problem solving.” Many traditional public schools, in contrast, follow a conventional structure where the instructor models, does guided practice, and students complete independent work. KIPP’s strategy of applied learning before conceptual mastery aligns closely with recent research and educational breakthroughs that just aren’t being implemented in public schools. Empirical research validates this, as studies from the National Bureau of Economic Research and Stanford’s CREDO (Center for Research on Education Outcomes) confirm that active learning and explicit instruction (two pillars of the KIPP model) yield significantly higher retention rates and conceptual understanding compared to passive instruction. In essence, KIPP prioritizes learning how to think over learning what to remember.

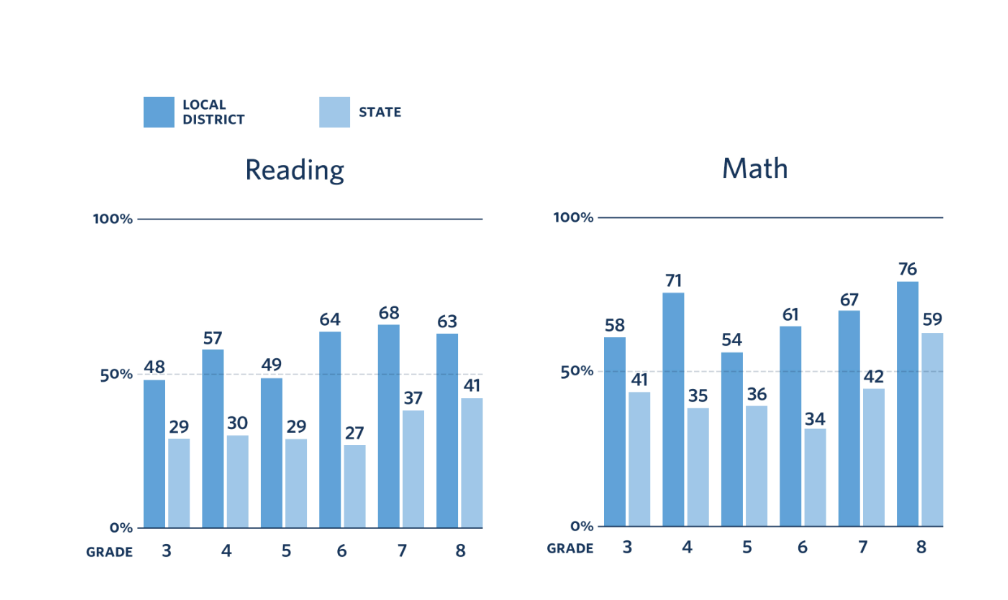

This difference in curriculum and structure between public and charter schools seems to favor the latter. The percent of KIPP classes outperforming local districts and states in 2018-19 in respective metrics and on aggregate can be visually represented below.

As seen through the charts, KIPP classes boast huge differences in performance on standardized testing, from a 17% difference in reading all the way to 37% in their respective grades. However, many professionals cast doubt on standardized testing as a proper indicator. According to the National Education Association, “standardized testing is an inaccurate and unfair measure of student progress,” citing concerns over a “one-size-fits-all approach to accountability.” Additionally, the phasing out and subsequent reintroduction of SATs and APs in the university admissions process makes it increasingly unclear as to academia’s stance on standardized testing: do these tests accurately determine whether or not students are learning and understanding the concepts they are taught? Two other important metrics that can and will be taken into consideration are student happiness and long term achievement.

Happiness is not only a consequence of a thriving economy but also a contributor. Analyzing data from over 100 countries between 2006 and 2018, provides some of the and using panel Granger causality tests (as well as other econometric models), found that increases in national happiness consistently precede and predict increases in GDP per capita, even after controlling for the usual drivers of growth. When people feel satisfied, supported, and optimistic, the economy performs better, possibly because well-being fuels productivity, creativity, and long-run economic dynamism. Thus, happiness is a crucial element of economic development, and a heavy consideration for analysis between charter and public schools.

Surveys conducted by KIPP’s National Student Well-Being Initiative (2020) show that over 84% of KIPP students report feeling supported by at least one adult at their school, compared to roughly 62% in national public-school averages. Additionally, according to longitudinal studies conducted by the Mathematica Policy Research Group (MPRC), KIPP students, despite spending longer hours in school, report equal or higher levels of satisfaction with their education than peers in traditional districts. This difference can be attributed to the sense of purpose and community built into KIPP’s design: the long days are not simply longer, but more personally responsive, filled with structured mentorship and individual progress tracking.

Crucially, this sense of belonging directly translates to higher long-term achievement. The MPFC in 2019 released a study tracking more than 15,000 KIPP alumni and found that they were 67% more likely to enroll in a four-year college and 47% more likely to graduate than demographically similar students who attended nearby public schools. That same study also gave insight into economic effects. KIPP graduates had significantly higher employment rates and were more than twice as likely to have salaried positions by their mid-twenties. Notably, when the share of college-graduates in a region rises by 1 percent, the wages of workers without college degrees increase by about 1.6 percent. This remains a strong indicator of broader labor-market uplift tied to higher education density. Expanding access to and completion of college-level education creates human-capital shifts that ripple through the economy, raising productivity, spurring innovation, and lifting overall growth.

Based on statistics alone, charter schools seem to perform better (according to the aforementioned reading and mathematics chart) in education and preparing students for long-term achievement. Some may argue that if only the most naturally gifted students or children with wealthy financial backgrounds are given access to charter schools, then the statistics aren’t properly reflecting the difference in education quality between charter and public schools for the average student. However, most charter schools admit students via blind lottery. This lottery mechanism is the strongest safeguard against schools only picking the cream of the crop and thus ensures representativeness within the applicant pool.

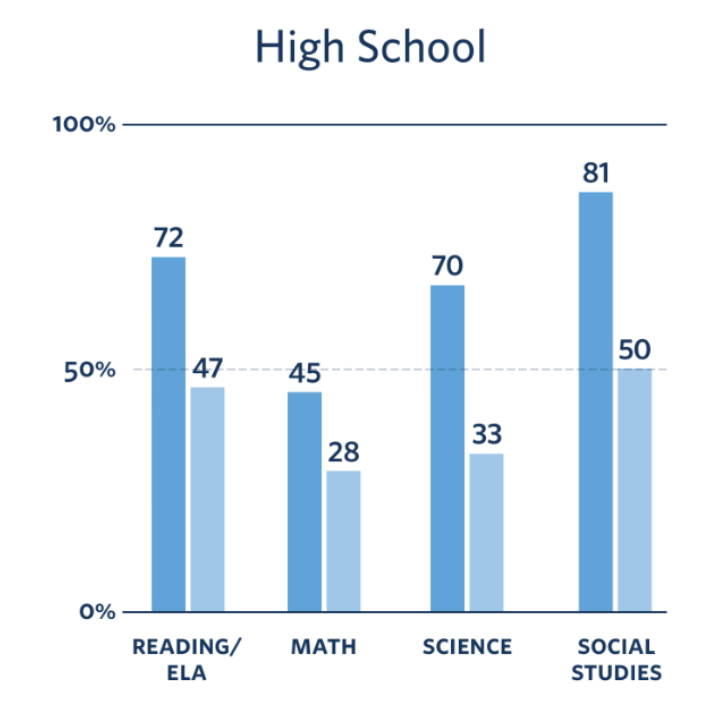

Figure 1. Percentage distribution of student enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools, by race/ethnicity: Fall 2012, fall 2022

The graph above shows enrollment demographics by ethnicity for public schools. Specifically, between fall 2012 and fall 2022, there was a decrease in the percentages of students who were White (51 to 44 percent), Black (16 to 15 percent), American Indian/Alaskan Native (1.1 to 0.9% percent. At the same time, there was an increase of Hispanic students (24 to 29 percent), and Asian students (4.8 to 5.5 percent). For charter schools, between 2012 and 2022, enrollment of Hispanic and Asian students increased (27 to 36 percent and 3 to 4 percent, respectively), while that of White and Black students decreased (36 to 29 percent) (from 36 to 29 percent and 29 to 24 percent, respectively.) These demographic patterns are not just descriptive, they determine which communities gain access to high-quality educational pathways that influence long-term economic mobility. What is key, however, is that according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), charter schools tend to be located in urban, high-poverty, high-minority districts. Because education is the primary engine of human capital formation, which students gain access to these alternative school models has direct implications for regional and national economic development. That’s important since these high-poverty and high-minority districts need systems and resources that bring new change more than any other group. This means that demographic changes in charter enrollment are not just reflections of national population shifts, they can be interpreted through the lens of representativeness. Most importantly, charter schools, which by the numbers are giving much higher quality of education and producing greater long term achievement are doing so for the people who have the least, not the most. In that way, charter schools serve to boost underprivileged communities and help their social mobility, which boosts economic development as a whole.

Social mobility strengthens an economy by unlocking human capital that would otherwise remain underutilized. When individuals can advance through education rather than be constrained by the socioeconomic status they are born into, a larger share of the population is able to participate in high-skill, high-productivity sectors. This increases the overall talent pool, drives innovation, and expands the tax base. Countries with higher levels of intergenerational mobility experience faster long-run GDP growth because economic success depends more on effort and skill than on inheritance. Conversely, low mobility traps capable individuals in low-opportunity environments, suppressing entrepreneurship and reducing labor productivity.

That said, selection bias at the charter school application stage remains real, with families who apply to charters are disproportionately engaged, informed, and mobile. This suggests that stronger academic performance can be found regardless of school type because even before instruction begins, charter schools enroll students whose families are better positioned to navigate complex educational systems.

As a result, charter schools may appear more effective not because of superior education, but because they attract students with higher baseline engagement and support. That means that charter-level gains may in a large part reflect differences in existing human capital rather than the creation of new human capital. Though this may be a concern, as the cream of the crop of the underprivileged communities are the ones who disproportionately gain access to resources for social mobility, I would argue that since it is a better system than the status quo, it should not be used against charter schools in an argument. Rather than keeping all disadvantaged students disadvantaged, like public schools, charter schools help the most intelligent and motivated groups of the disadvantaged students. When comparing the both, it is a zero sum game, making it clear that charter schools provide better economic opportunities in comparison.

I have spent a long time indirectly singing the praises of charter schools, but there is more nuance to be found and considered before fully embracing charter schools and hailing them as the greatest catalyst of economic development. There’s two key criticisms from opponents of charter schools: resource diversion and inefficient allocation of resources.

When charter schools draw students away from traditional public districts, the accompanying transfer of funding can leave public schools with the same fixed costs but fewer dollars. As charter schools increase their students, local districts may lose $300 to $700 per remaining public-school student. In some cases, the loss has been estimated at $700 to $1,500 per student for remaining district schools. In New York, research estimated that the districts of Albany and Buffalo faced fiscal impacts of about $633–$1,070 per public-school pupil linked to charter expansion. These losses matter economically because weakened public-school funding undermines the mass human-capital formation needed for broad-based productivity gains. With fewer resources, districts may reduce teacher quality, cut enrichment programs, or delay infrastructure. Needless to say, that is quite damaging for economic development. It creates an all or nothing game where the implementation of charter schools necessitates full implementation, or risk competition which slaughters public schools and harms the students there. What’s important to recognize is the growing pains with this approach as well. It is impossible to implement enough charter schools to replace an entire district at once. Thus, phasing out an entire district over the course of a decade would require times when public and charter schools are coexisting in the same district, leading to tens of thousands of students to potentially be negatively impacted by this transitional phase.

This argument hinges on the belief of preventing progress to prioritize a small minority of students rather than the future majority of students who would benefit. As far as problems go, doing “too well” and beating out the competition, public schools, is a fairly good problem to have. In fact, going back to the history of the charter school system, this was President Ronald Reagan’s intention. His vision was that competition would force public schools to innovate, become more efficient, and improve instructional quality, ultimately raising the performance of the entire system. From this perspective, resource diversion is not a flaw but a feature: if funding follows students, then schools that cannot attract or retain families are incentivized to reform.

It has been established that education is a priority for building a robust economy and strong nation. The point of contention lies in what is the best way to execute that education, whether through private or charter schools. Charter schools, publicly funded but independently operated institutions designed to foster innovation within the public education system, have shown to outperform public schools on several key indicators: long term achievement, standardized test scores, happiness, and social mobility. All four of these metrics are crucial to economic development, and charter schools’ massive lead in all of them shows that charter schools are the system to break the status quo and educate Americans in a smarter, innovative, and enjoyable way.

Photo by KIPP

Abhimanyu Sharma is a freshman at New York University studying Math and Economics. He has had numerous entrepreneurial ventures in tech and education, and hopes to continue his startup journey. He also enjoys political discussion, travelling, and reading.